An exotic annual grass fuels wildfires that weaken or kill native plants on intermountain rangelands. A native insect can help us reestablish desirable native plants in areas now dominated by this weedy grass.

Native army (miller) cutworms (Euxoa auxiliaris) eat exotic cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum) and the mustards (Brassicaceae) that often grow with it. During their periodic outbreaks, the larvae create widespread cheatgrass die-offs in low, dry areas in the intermountain West. These die-offs are an opportunity to establish preferred species.

Most cheatgrass seeds germinate as soon they have enough moisture during cool temperatures. This reduces the cheatgrass “seed bank” in the soil. When army cutworms eat all the seedlings in an area, no more seeds are added to the seed bank. Most of the cheatgrass seeds that didn’t have enough moisture to germinate in one year are eaten or killed by fungi before the next growing season. We can capitalize on this temporary dearth of cheatgrass seed by reseeding die-offs with native perennial species. This will give the sown plants a head start on cheatgrass.

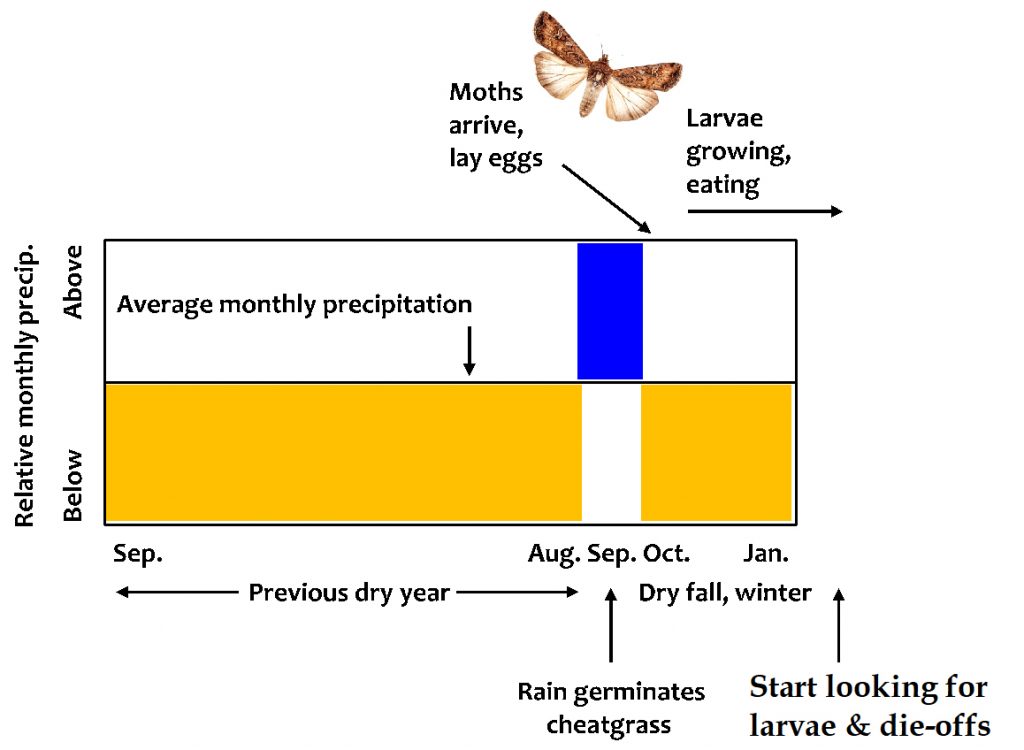

Extensive die-offs first appeared in 2003, during a widespread army cutworm outbreak. The outbreak and die-offs occurred after:

1. a dry winter, 2001—2002, allowed many larvae to survive, pupate, and emerge as adult moths,

2. heavy rain in late summer 2002 provided moisture for cheatgrass to germinate in fall,

3. a large flight of adult moths laid eggs in fall 2002, and

4. a second dry winter, 2001—2002, allowed many larvae to survive and eat cheatgrass seedlings.

My 2004 research poster described how army cutworm outbreaks can lead to cheatgrass die-offs.

I recognized the same conditions again in January 2014 and found army cutworms in cheatgrass die-offs in late February in Owyhee County, southwest Idaho. My research paper documented larval damage to cheatgrass, mustards, and native shrubs, and followed the subsequent recovery of vegetation.

What are army (miller) cutworms?

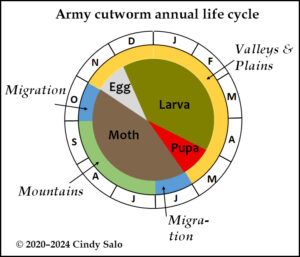

Army cutworms are native migratory insects, found in arid regions of the western United States and Canada. The adult moths are called miller moths. This native species feeds on seedlings of many exotic weeds and crops.

Army cutworms create cheatgrass die-offs while hiding in plain sight. They spend the winter hiding in the soil or under cowpies during the day and eating seedlings at night. The larvae find and eat all seedlings within an area. In late spring, the larvae pupate and emerge as grayish-brown miller moths. The moths eat nectar and follow the blooms of flowering plants up to mountains for the summer.

Miller moths’ tiny wings carry them on impressive journeys. Moths emerging in the Great Plains fly through Colorado’s Front Range on their way to high peaks in the northern Rockies, where grizzly bears wait to feast on their fat-filled bodies. Miller moths emerging in the Intermountain West seem to spend summers in nearby mountain ranges. “Blizzards” of moths summered in Great Basin National Park after army cutworm outbreaks and cheatgrass die-offs in 2014, and black bears munched on millers in the Jemez Mountains of northern New Mexico in 2003.

I’ve studied these intriguing insects and the cheatgrass they love to eat since 2003. My “trapline” monitors fall miller moth numbers in southwest Idaho, where sharp-eyed residents help watch for army cutworms in winter and cheatgrass die-offs in spring.

When we understand army cutworms enough to predict their outbreaks, we’ll know when and where to look for die-offs. When conditions that lead to army cutworm outbreaks occur though the end of January, it’s time to start looking for larvae and die-offs.